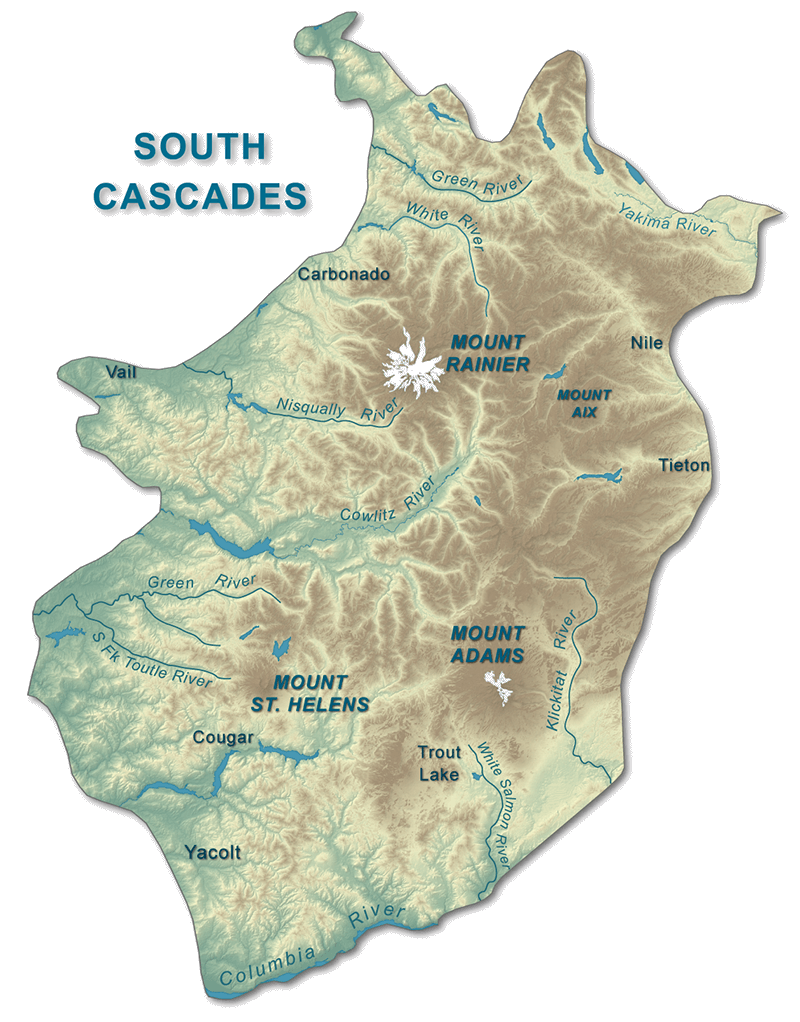

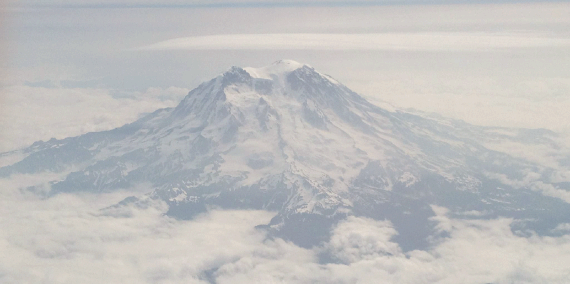

The South Cascades Province in Washington extends from the Columbia River to the south and Interstate 90 to the north. The southern Cascade Range skyline is dominated by three massive stratovolcanoes: Mount Rainier, a towering giant with the highest elevation in Washington of 14,410 feet, Mount Adams, the second highest peak in the Pacific Northwest with an elevation of 12,276 feet, and Mount St. Helens, the youngest volcano in the Cascades with an elevation of 8,366 feet. The volcanoes we see today are the most recent installments of a 40 million year old volcanic complex called the Cascades Volcanic Arc.

Terrane Accretion

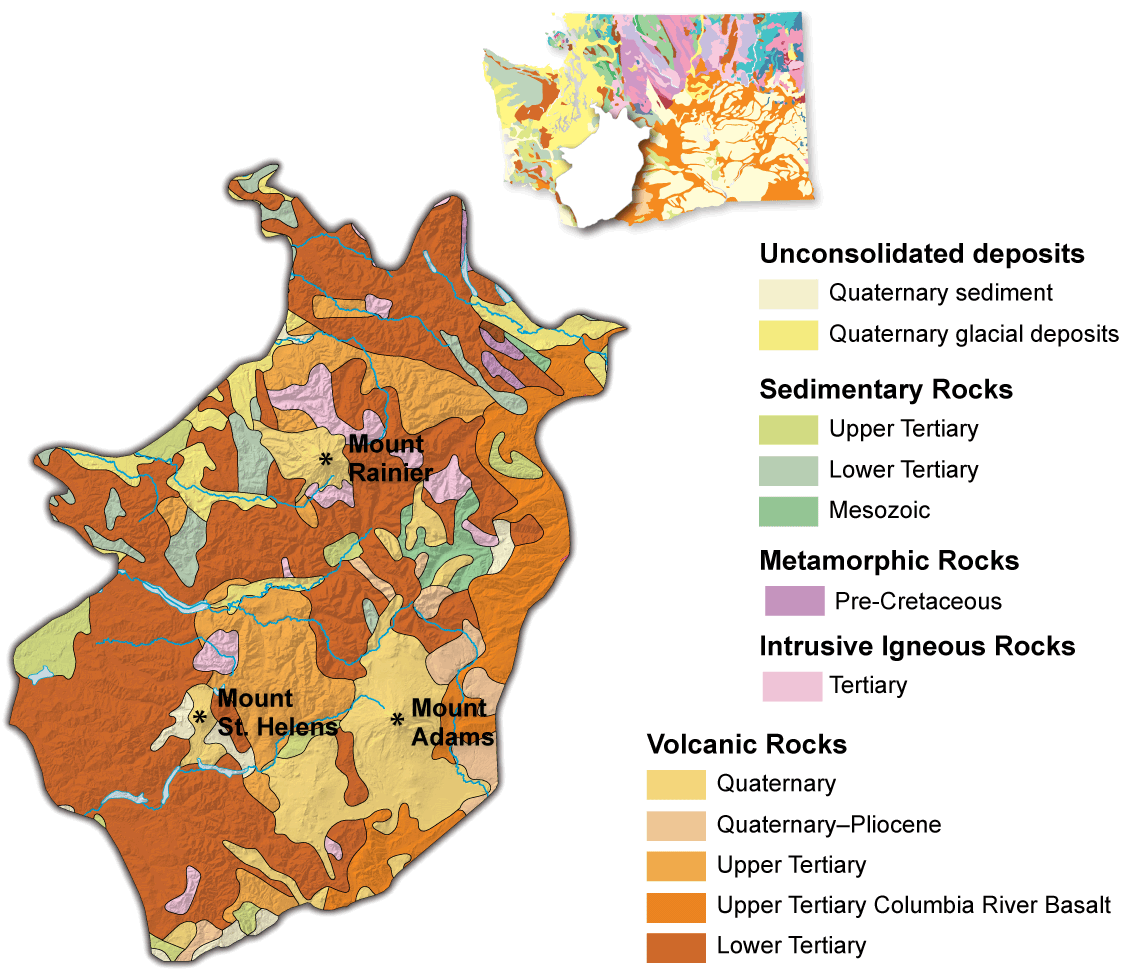

The early geologic history of the Southern Cascade Range is much the same as the North Cascades. About 200 million years ago, the dense oceanic Farallon plate began subducting beneath the thicker, more buoyant continent of North America. As the oceanic slab sank and subducted, ocean floor sediments, volcanic island chains, and basalt that was erupted from underwater volcanoes were all scraped off of the oceanic plate onto the continent during a period of accretion (addition of material). The subducting oceanic plate went under the continent where it melted the surrounding mantle. The melted material above the subducting oceanic plate eventually erupted as a chain of ancient volcanoes and plutons.

Between 55 and 43 million years ago, before the formation of the Cascades, basalt from the subducting oceanic slab was being accreted. The Siletzia and Crescent terranes are two packages of rock that represent this period of accretion and can be found in the southern Cascade Range today.

Eocene Basins and Early Cascade Volcanism

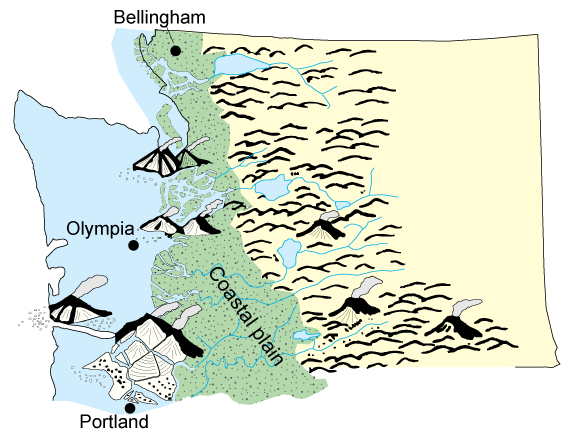

During the Eocene, between about 55 and 43 million years ago, the ocean shoreline was located near Interstate 5, and ancient granitic mountains were located east of the present-day Cascade Range. Rivers drained these ancient mountains, and massive amounts of sediment were carried along these rivers and deposited in shallow marine basins. These sediments are now preserved as the sedimentary Cowlitz Formation and Puget Group. Much of western Washington was a coastal lowland, or swamp, where an enormous amount of vegetation grew and was later buried by the sediment that came from the rivers draining the mountains. As the vegetation was buried, high pressures and temperatures converted it to coal. Some leaves, wood, and plants from this swampy environment are preserved as fossils.

Paleogeographic map of the coastal plain of western Washington during Eocene time. Modified from Brownfield (2011).

The earliest Cascade Range volcanoes began erupting around 43-37 million years ago in the coastal plain environment. Many of these volcanoes erupted mafic (dark-colored, low-silica) lavas such as basalt and andesite. Some volcanoes erupted felsic (light-colored, silica-rich) lava and ash. The Rockies, a small mountain range northeast of Morton, Washington are remnants of the volcanoes that erupted in this interval and produced the Northcraft Formation.

After the eruption of the Northcraft volcanoes, the early Cascade volcanic arc began erupting east of the Rockies from around 37 to 17 million years ago. This was a large volcanic arc, spanning from southern British Columbia down into California. These volcanoes erupted at a fast pace and covered the land with a massive outpouring of lava, ash and various rock fragments. The volcanic rocks of the Ohanapecosh Formation, the Hatchet Mountain Formation, and the Goble volcanics were erupted during this time. Together this pile of volcanic rock is around 6 miles (10 km) thick! These old cascade volcanoes were eventually eroded and buried by the next episode of volcanism, and today only the deposits left by the oldest Cascade volcanoes tell of their existence. From ~27 to ~22 million years ago, the ancient Cascade volcanic arc experienced many more volcanic eruptions and pluton intrusions which covered the Cascades with lava, ash, mudflows, and plutonic rocks (granite type rocks). The Fifes Peak volcanics, Bumping Lake granite batholith, and the Spirit Lake Pluton are a few of the main rocks from this episode of volcanism.

Columbia River Basalt Group

Following the last phase of volcanic activity there was a time of erosion and uplift. Gentle folding and tilting of the older volcanic and plutonic rocks occurred from ~21 to 18 million years ago. This lull in volcanism didn’t last long, because starting around 17.5 million years ago huge amounts of basalt flooded the southern Cascades, issuing from linear vents, called dikes. These extensive basalt flows are called the Columbia River Basalt Group and they cover much of southern Washington and northern Oregon. Numerous dikes and sills intruded the volcanic rocks from ~12 to 10 million years ago after the initial outpouring of flood basalts.

Interactive diagram showing volume and area of all of the Columbia River Basalt Group formations and the major members.

Modern Cascade Volcanism

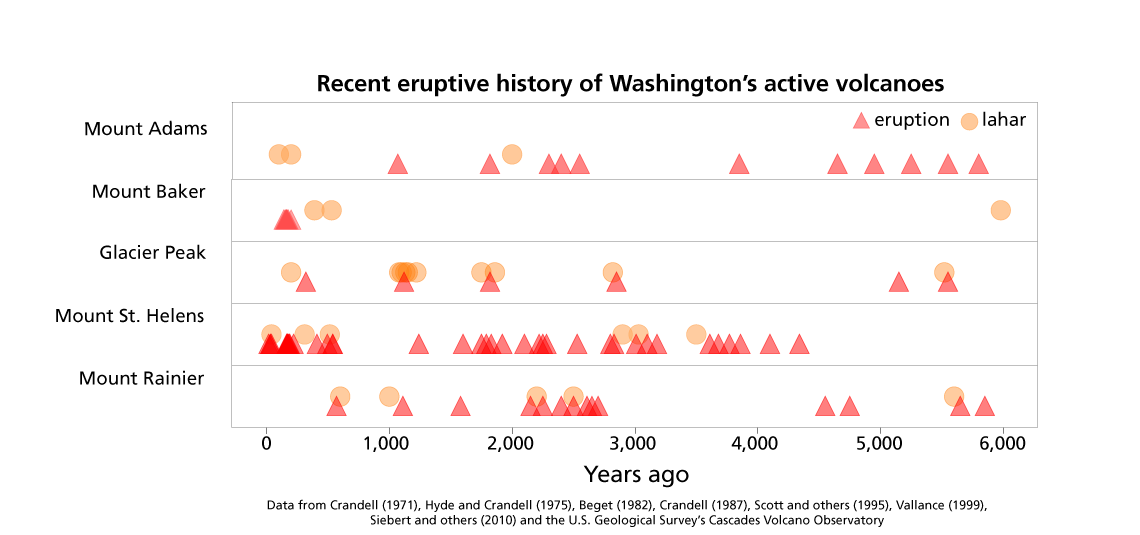

For the last 40 million years, the subduction and melting of the oceanic Juan de Fuca Plate beneath the continental North American Plate has generated the magma that spurs volcanic eruptions in the Cascades Volcanic Arc. The most recent chapter of volcano building began ~500,000 years ago; Mount Rainier, Mount St. Helens, and Mount Adams are products of this period. Evidence of repeated eruptions from these volcanoes exists in the geologic record.

- Mount Adams

- Mount Rainier

- Mount St. Helens

-

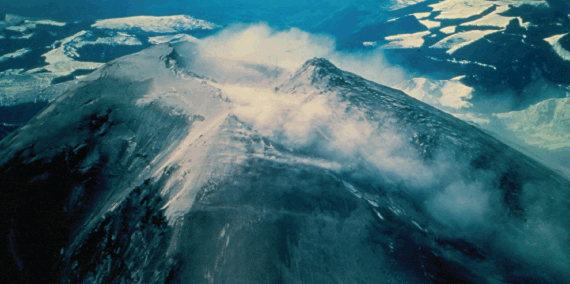

Mount Adams is the largest volcano, volumetrically, in the Pacific Northwest. It is actually a cluster of volcanic vents that erupted andesitic lava from the vent cluster rather than a single vent. The Mount Adams system is one of the youngest in the Cascade Range. The volcanic center first erupted 520 to 500,000 years ago, and continued up to about 1,000 years ago.

There have been no historical eruptions in the Mount Adams volcanic field. However, there were a series of debris avalanches and lahars between ~600 and 300 years ago.

Hydrothermal alteration is present on the main cone as well as at numerous locations along the slope. Fumarole activity was reported at the summit from miners trying to extract sulfur from the crater in the 1930’s, but later reconnaissance trips did not see any fumaroles, only the faint smell of sulfur.

Mineral Deposits

The two main mining areas in the Southern Cascades are the St. Helens and Washougal Mining Districts. Metal deposits are typically found in small fractures and veins within the rocks and contain predominantly: pyrite, magnetite, chalcopyrite, bornite, galena, and sphalerite; with lesser amounts of: copper, zinc, lead, molybdenum, gold, and silver. Minerals that can be found in the area include: azurite, malachite, tourmaline and chrysocolla.

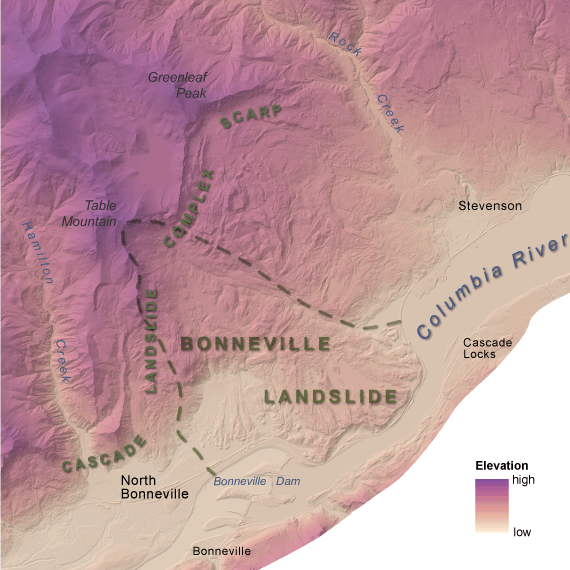

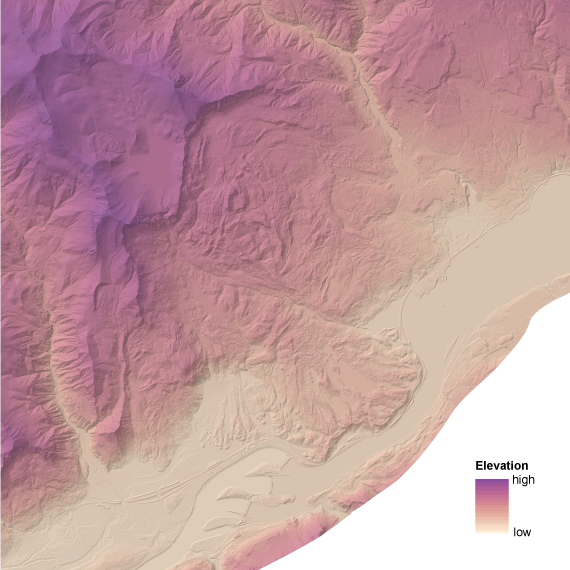

The Bonneville Landslide

The Bonneville landslide is a massive landslide in the Columbia River Gorge about 30 miles east of Portland, Oregon. The slide covered an area over 6 square miles and temporarily dammed the river, creating a large lake. Native American legend refers to the slide as “The Bridge of the Gods” referring to the massive amount of land that slid from the hills to the north. The land blocked the river, creating a temporary land bridge. Lewis and Clark noticed the slide on their journey in 1805, stating that the river was “obstructed by the projection of large rocks, which seem to have fallen promiscuously from the mountains into the bed of the river". The Columbia River has since reclaimed its path, and the Bridge of the Gods is now made of steel.

The area around the Bonnevile landslide is especially prone to sliding. Weathered, clay-rich volcanic sedimentary rocks of the Eagle Creek and Weigle formations. Beds in these formations dip toward the Columbia River and are overlain by basalt flows at the top of the section. The basalts periodically slip toward the river upon the clay-rich beds. Geologists and dendrochronologists (scientists who study tree rings) are still figuring out exactly when the slide happened by examining the trees that were demolished during the slide. The best estimate is that the slide happened around 590 to 570 years ago.

The Bonneville landslide is actually part of a larger complex of landslides, called the Cascade Landslide Complex.